I cannot expect you, my reader, to understand how I came to be a Rastafari. I was not born in the Caribbean, and I was not born to the descendants of enslaved Africans in the West (though we suspect there are some in the lineage). I was not raised as a Rasta, but this is something that happened to me. It is the work of JAH (God).

Neither can I fully explain here at this time how I came to be an Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Christian. That is likewise mysterious and incomprehensible. But, I will give some highlights of my journey, and I will tell the story of how I became baptized at the Qidist Selassie (Holy Trinity) Cathedral in Addis Ababa at Fasika/Tinsae (Ethiopian “Easter”) of 2018 AD (2010 Ethiopian Calendar).

How I Got Here

My parents were not quite Rastas, but they were “rootsy”. They lived in a treehouse among the foothills of the North Cascades Mountains, at the bottom of a trail through the woods near Hansen Creek, where they kept a large garden. When my baby brother was conceived, they cleared out the garden to lay the foundations for a house, and we moved out of the tree, onto the land, when he was born. It was an idyllic, heavenly setting, but it was placed just next to the borders of Hell.

A few months shy of 4 years old, I was molested by the son of the daycare owner, less than a mile from home. This led to a court trial, where I was made to testify, and to years of counseling. Soon after, attending Kindergarten in the town of Sedro-Woolley put me directly into the middle of the ethnic, racial, and religious confrontations of the American Frontier. I was quizzed and questioned and bullied and harassed for not fitting into one of the ethnic or racial boxes proscribed, nor having a religion to represent for on the battlefield.

It was around this time that I began to invent “my own religion”. Through a series of recurring dreams, some profound experiences alone in the deep forest, and the “Tent Revelation” (when at 6 years old I took a stack of Bibles and other religious or mythological books into a tent to pour through them over a weekend and emerged with my own set of conclusions) God and I together set the foundations of a personal philosophy that has been my guide–and my struggle to live up to–until this day.

No one taught me how to pray. I learned to pray directly through fear of God, in terror, utter humility, and absolute faith. But I did not learn to fear humans, I learned to stand up to them. I’m not saying I was morally correct, and I definitely didn’t know how to turn the other cheek. From the 2nd grade until 20 years old, I was in at least one fistfight per week. Some of those fights involved bats, bottles, knives, or bricks… But this isn’t my whole life story, just the important highlights of my spiritual progression.

I excelled as a learner. I read a lot of books and was involved in many gifted programs and extracurricular activities. Some of those books deeply affected me. I was also informed by experiences with religious missionaries, visits to various churches, and a brief stint in the Baha’i faith. I studied history, philosophy, religion, and politics. In the Bible I read, “I Am That I Am”, and “Love Your Neighbor As Yourself.” In Stranger in a Strange Land, I read, “Thou Art God”. In the Autobiography of Malcolm X, I read about the Marcus Garvey movement.

When I was 9 years old, the band Nirvana blasted onto the scene and changed the world of American popular music. I started to obsess over bands, and to dig through my Dad’s record cabinet, making bootleg tapes of his vinyl. One of those records was Bob Marley’s “Rastaman Vibration”, featuring the song “War”, which contained the words, “Until the philosophy which holds one race superior and another inferior is finally and permanently discredited and abandoned, everywhere is war,” taken from a speech of Haile Selassie I. The words of this song became part of my personal religion.

“Until the philosophy which holds one race superior and another inferior is finally and permanently discredited and abandoned, everywhere is war.” – Lyrics to the Bob Marley song ‘War’

I wound up devoting my life entirely to the underground music scene and street culture. I was a Skater and an Anarcho-Punk first, and then a Skinhead (not a Nazi, or a white supremacist, I was a traditional & anti-racist skinhead), a graffiti writer, zine maker, and a drummer in hardcore punk bands. I immersed myself in Ska, Rocksteady, Reggae, Punk, Oi!, Hardcore, and Hip-Hop music. These subcultures, scenes, or movements, became my armor against the world, as well as my entree into the world. I traveled the West Coast and the East Coast, hanging with Skins and Punks, and then moved into the heart of the city (Seattle) to be where all the action was. Throughout this period I often told people that I was a Rasta, and everyone took it as a joke, except for the real Rastafari people I met from time to time in East Coast cities. They were the only ones who took it seriously and gave me little bits of wisdom into the thing, which I really knew next to nothing about.

Mine was no monastic life, and it was no white picket fence thing. It was rough and tumble. I was in a lot of fights. I worked every kind of low-level job from washing dishes to digging holes. I saw a lot of loud, aggressive live music. I got in a lot of trouble. In a series of events during 2001-2002, I lost one of my best friends to a drunk driver, saw the twin towers come down, lost the use of my dominant hand by breaking it in a fistfight, got addicted to pills, had guns pulled on me 4 times over a 2-month span, and eventually decided to leave the city and return home.

Then, in early 2003, I tried to move to LA, my appendix burst and I nearly died. I had an out of body experience. I returned home for 12 weeks of bed rest. At that time, I wanted to make something more of my life, and decided that I would go to college. Returning to Seattle, I attempted to hide out, avoiding many of my old associates and old patterns. That was when my brother died, at age 19, in the Iraq war. I was brought face to face with death and mortality. There was no time to waste.

Then I started a career and I went to college, held down a long-term relationship, and got very serious about my health and physical fitness. I began to smile and enjoy life more, and to experience some success in it. But there was still a lot of darkness, negativity, and pessimism mixed into my whole thing. I had a lot of self-hating and self-sabotaging thoughts or behaviors. The violence was less, but still present. Alcohol, drugs, and risky sexual behaviors were definitely still a problem.

Late one New Year’s Eve, on December 31st, 2005, my best friend died in my arms, and I had to bring him back to life. After that insane night of partying and regretful experiences, I knew it was time for things to change. Early the next morning, on New Year’s Day, January 1st, 2006, while reading an in-depth article about Bob Marley and his faith, I made a vow to grow my hair and respect the Divine within myself, to put this Rasta consciousness on the outside as an identity and change my ways. It was not an overnight change. My hair was growing, but all my friends and associates and surroundings were still the same.

After graduating from University of Washington later that year, I left the USA and traveled the world. Much of that story was told on my travel blog in 2006-2007. During that journey, I removed myself from the mass of western tourists and tried to become grounded with the people. That was when I met Chelly, my wife to be, and surrendered my heart to love. I explored Buddhism and Hinduism and began to read the Bible in depth. I quit drinking alcohol and experienced a change of heart, resolving to turn away from selfish living and seek righteousness.

After she took me to Kenya in early 2007, Chelly’s brothers introduced me to the Rastafari bredren there. The seed that was planted in my heart by Bob Marley’s lyrics, and nurtured through the vow to grow my hair, now began to grow and bear fruit. I met many Rastafari bredren and sistren in Mombasa at that time, and I heard a great many reasonings that taught me many things. For the first time, I was really learning about Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia and the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.

Later that year, in Seattle again, I started up a conversation with an Ethiopian parking lot attendant. I asked him if there was an Ethiopian Orthodox Church in town and he directed me where to go. That Sunday, I attended St. Michael’s Church from 5am to 5pm. This period of life was also one of profound religious seeking. I’d been to Churches, Temples, Mosques, and Synagogues on four continents, but at the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, I felt I’d found THE PLACE where Heaven and Earth were one.

I attempted to be baptized several times over the following years, but was prevented. First, by Ethiopian priests in Seattle who didn’t want to baptize me because I was a Rasta, or because I was of Greek origin (Greeks have their own Church), and by Greek priests who didn’t want to baptize me because I was a Rasta, or because I was attending Ethiopian Church (at the time they were united on paper, but not in fact), and later–while living in Kenya and planning to fly to Ethiopia for baptism–by the untimely death of my father-in-law. After that, life became heavy and challenging again. The thought of baptism didn’t leave me, but it became lower and lower on my list of priorities.

I continued to ground with the Rastafari family in Seattle and in other places where I was living and traveling, such as Thailand and Kenya. I attended Nyahbinghi Ises, avidly studying the works and words of Haile Selassie I, and the Bible. The words of Haile Selassie I taught me a greater appreciation for the Bible, and instructed me on the reasons for Orthodox Christian faith, as well as how to apply it in all aspects of life. Meanwhile, the words of the Bible increased my appreciation of Haile Selassie I, and I began to see the bigger picture of integrity within a faith in His Majesty and a faith in Iesus Christ.

Then, during a month-long family trip to Kenya in 2018, baptism came to the forefront again.

Ethiopian Holy Week

Kenya and Ethiopia are neighboring countries, and through their common history of resistance to colonialism, they share a strong bond. Jomo Kenyatta, the independence leader and first president of Kenya, was a disciple of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I, one of His Majesty’s supporters during the Italian invasion, and was likewise supported by the Emperor during the post-World War II period of African independence struggles. They were often seen together at the Organization of African Unity headquarters, or touring one another’s countries together in the back of a convertible. Kenyans’ affinity for Ethiopia has been further strengthened by the popularity of Reggae music in the country, and there are countless Rastafari people there.

During this month-long trip to visit relatives in Kenya, there were a lot of people talking to me about Ethiopia. By this time in my life, I knew many Kenyans, and many of them were Rastas, and they all knew I was a Rasta, whether I had the dreadlocks or not. At some point, someone told me this upcoming weekend was the Ethiopian Easter. I’m not sure if it was the Rastas or some non-Rasta friends who’d seen it on the news, or what, but I asked Chelly if we had anything planned–and seeing the dates were open–I booked a flight to Addis.

I flew on the evening of Holy Friday, landing in Addis Ababa and heading straight to my little guesthouse just outside the city center. I ate my dinner there, and remember distinctly struggling with the in-line electric water heater and taking a cold shower. Then it was early to bed. In the morning, I wandered the neighborhood and found a back-alley bodybuilding gym. All the equipment was made from repurposed metal scrap, such as old car and truck axles. I was thrilled to find this place and got a great little workout in before heading back to my guest house for another cold shower. Then I was off on my mission.

The first thing I noticed about Addis Ababa was that it is a holy city. Everywhere I went I saw the palm leaves that had been spread for Hosanna (Palm Sunday) six days earlier. They were on the sidewalks, they were in the restaurants and shops, they were even in the aisles of the busses. It was on one such bus, adorned with holy icons–and, to my approval, a photograph of Emperor Haile Selassie I–that I encountered a brown-robed monk-priest with his distinctive hat and long prayer rod.

I sat down next to the priest and told him my story. I told him about approaching Rastafari through the music of Bob Marley and the dreadlocks covenant. I told him about coming to Africa for the first time and meeting the Rases in Kenya. I told him about attending the Ethiopian Church in Seattle, and about my decade moving with the Rastafari community there. I told him about following His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I, who had taught me about the philosophy of Orthodox Christianity, the history of Ethiopia, and the value of a Christian life. I told him about the conflicts I’d seen in Seattle amongst the Ethiopian churches who’d split from one another, about my desire to be baptized, and being blocked by prejudice or unfortunate circumstances. Then I told him about the Ethiopian Eunuch.

This story is quite well known in Ethiopia, but you may not have heard it, so I will repeat it here briefly. It comes from the Book of Acts, chapter 8, verses 26-40, in the New Testament. This passage tells of an Ethiopian Eunuch, treasurer in the court of the Queen, Candace, who had traveled to Jerusalem for worship. Returning home in his chariot, he is met by the Apostle Philip, who helps him to understand a passage from the Prophet Isaiah. The Ethiopian asks Philip to baptize him, and they descend to a body of water at the side of the road, where he is baptized. He then brings Christianity into Ethiopia. It is taken as an example of the urgency of baptism.

I told this priest that I wished to be baptized in this way, like the Ethiopian Eunuch, just take me to some water on the side of the road and let me be baptized. Then he looked at me silently. A moment of anticipation… Then, he put his finger to his lips and intoned, haltingly, “No… speak….” Oh no! This man didn’t speak English. But then he relieved my despair, reaching forward to tap the shoulder of one of the men seated in front of him.

These were two Deacons from the theological school who spoke excellent English and had heard my entire story. After a brief exchange with the priest, they vowed to help me, and we got down from the bus. They then proceeded to take me on a tour of the area of Arat Kilo, where Emperor Haile Selassie I had donated his personal palace and family lands for the establishment of a University, and had constructed an ornate cathedral.

The tour began in the former palace, now a museum decorated with a few scant artifacts from the Emperor’s time. A robe here, a bed there, a framed mirror. It wasn’t much, most of the Emperor’s personal effects having been looted or destroyed during the brutal Communist coup of the 1970s. Nonetheless, I felt profound emotion in this empty palace, the former home of a man whom I had in fact worshipped as the living God, who–through studying his words–had taught me the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, the awesome wonder of the Incarnation, the importance of Baptism, the sacred mystery of Communion, and the promise of the Resurrection. In following his footsteps, I was now prepared to die and be born again into Christ’s Kingdom.

There I remembered many stories, myths, and legends I had learned from the Rases over the years. You can’t find this stuff on the internet, or even in books. Most of Rastafari culture is orally transmitted, and in my dozen years of openly trodding Rastafari by this point, I had spent time reasoning with Rastas in America, Jamaica, Kenya, Tanzania, and Thailand, and I had accumulated a lot of this oral history. Looking through the various rooms, seeing the robes or uniforms hanging on the walls, I was reminded of the lore of Rasta now being transmitted from ear to eager ear all across the African continent and abroad.

Then the Deacons took me to Holy Trinity Cathedral.

Menbere Tsebaot Qidist Selassie

Holy Trinity–or Qidist Selassie, as it is known in Ethiopia–is also called Menbere Tsabaot (the Altar of Victory). Built by Emperor Haile Selassie to commemorate his victory over the Italian Fascist invaders in World War 2–and to house the remains of His Majesty’s daughter, who died during the war–it is the national cathedral of Ethiopia and seat of the Patriarch. It is a massive and splendid cathedral, surrounded on all sides by a cemetery for the nobles and notables of Ethiopia. There amongst the final resting places of Ethiopian priest and politicians is found the graves of English suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst, an early supporter of Haile Selassie I and lifelong friend, and her son Richard Pankhurst, a nationalized Ethiopian and noted scholar.

After engaging a tour guide we were taken inside the church. The first thing to greet us was a large icon of the Holy Mother and Child, hanging above the entry way. This painting commissioned by the Emperor portrays Haile Selassie I and Empress Menen Asfaw bowing down to Christ and His Mother. Suspended on poles in the middle of the vast cathedral were the actual flags in use by the Emperor and his personal retinue. This was the only place where I saw the Imperial standard flying in Ethiopia. Not only was there the famed Lion of Judah flag that we Rastas use today, but also the Emperor’s personal flag adorned with 7 stars of David and with St. George slaying the dragon on the back side. Additionally, there were the military flags, such as the Imperial Naval standard that flew on His Majesty’s flagship.

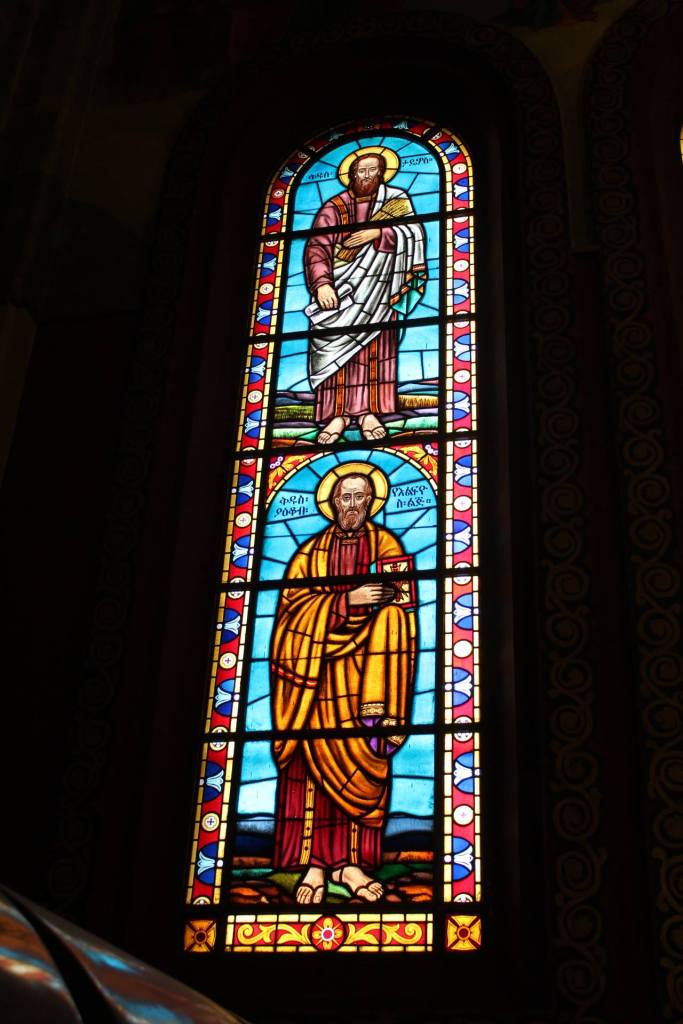

Around the outer walls of the cathedral were massive stained glass windows depicting the stories of the Bible, from Genesis to Revelation. Then, up at the front of the church near the Holy of Holies, were walls of painted icons. I had expected all of the icons in the church to have been of Black people, showing all the Biblical figures as Africans, as I believe them to have been historically. To my surprise, however, it was a mix. The figures in the stained glass looked like Caucasians, while the painted icons up front appeared African, and the Mother and Child above the entryway were mixed–“Habesha” or “Abyssinian”–in appearance. The great dome in the center showed a Black Christ sitting in final judgment at the end of time.

Also at the front of the church and inside the base of the great dome were portrayed the important events in the life of Emperor Haile Selassie I: His appeal to the League of Nations, the liberation of Ethiopia, the gatherings of the Organization of African Unity and the councils of Orthodox Bishops and Patriarchs over which His Majesty presided. Seated below these historic images were two elaborate thrones: one for Emperor Haile Selassie I and one for his Empress Menen Asfaw. These were the thrones they used when attending the communion mass (Qedassie) in this church.

And then there were the tombs…

On the left flank of the Holy of Holies sat two massive stone sarcophagi. One is known to contain the remains of Empress Menen, whom His Majesty had interred there in 1962. The other is reported to contain remains of His Majesty–installed in the tomb during a low-key funeral in the year 2000, after spending 8 years on public display in the basement of the church, having been dug up in 1992 from beneath a DERG-built latrine outside one of His Majesty’s former palaces. I did not at the time, and still do not, believe that these remains are genuinely those of Haile Selassie I. Many issues regarding their authenticity have been raised, such as the length of the bones being too large for His Majesty’s diminutive stature, and the lack of teeth to be able to match with dental records.

When His Majesty disappeared from the public eye in 1975, the DERG regime claimed that he had died of natural causes, but were unable to produce any photographs of his corpse, or to present a body for medical autopsy. They simply made the announcement and then moved on with the matter. There was no funeral. Many family members and close associates refused to believe he was dead, restating this doubt in numerous interviews on radio, television, and in print, which are easy to find today. Then, with the exhumation of these remains in 1992, the whole story changed. The new (still communist) government provided a trial, in which the tale of an alleged strangling by deposed dictator Mengistu Haile Mariam was entered into the official record. This is the same government who held the funeral 8 years later, and most Rastas consider the entire matter to be fabricated for the purpose of political theater.

I knelt and prayed, touching the tombs, before I left the church, imploring the Almighty for peace and blessings upon the remains of those within–for Empress Menen–and for the man, whoever he may be.

The deacons instructed me to go buy a white shawl to cover myself with, and to return to the gate of the church grounds at 10pm that night for my baptism.

My Baptism

After picking up a white Natela (shawl) and having a nap, I returned to the church gates at 10pm. The scene is something I must take pains to describe. It affected all of my senses and emotions. I have photographic memories of it, but it may actually be difficult for others to picture if I don’t pick my words right. So I’ll try.

Addis Ababa is built amongst mountains at about 8000ft above sea level. On the mountain tops, scattered all around the city, sit Ethiopian Orthodox churches. On this night, the holiest and most important of the year, each of these churches was alive with light and sound. This was the time of “Fasika” (Pascha, or Passover), the culmination of Christ’s Passion, the last night of Holy Week, the Great & Holy Sabbath, the eve of the feast of “Tinsae” (Resurrection), also called the Ethiopian Easter–though this term is incorrect, referring as it does to a Babylonian pagan deity (Ishtar) and not to Christ.

As I walked from the guest house to the taxi stand, I saw many others in white clothes, white shawls over their shoulders, also beginning to make their way to various churches. Driving through the city, I saw many of these churches, and when the taxi cab dropped me in the Arat Kilo neighborhood, I was able to walk slowly and appreciate what was happening around me.

On all sides I saw progressions of the faithful, clothed in white, carrying candles as they approached the numerous churches. Even in the far distance, I could make out twinkling candlelight and white cloud-like figures ascending the hills to their church buildings. And then there was the sound. Echoing across the city were the haunting Ge’ez chants, the ancient Ethiopic language still used in church services, in which the ENTIRE congregation uses their voices as an instrument for the praises of God. More people may be familiar with the Muslim call to prayer, which was in fact derived from the Ethiopian chanting tradition when Belial (the first Muezzin), an Ethiopian, returned with Muhammad’s family to Arabia after the First Hijra and introduced the practice there. Now imagine that call to prayer, but in a Christian context, and being broadcast not by a loudspeaker, but by the voices of all the faithful. The sound was otherworldly.

Approaching the Church, I encountered many things I was not prepared for, such as the sheer mass of people, the sellers of candles, and the many ill and infirm people (including the haunted or possessed, the crippled, and the mad) who gathered around the entrances to the church grounds aggressively begging for alms. As I waited for 30 minutes at the church gate, I was really overwhelmed by the sights and sounds of it all, and my mind was turning in circles of conflicting thoughts.

Here I was, about 12 thousand miles away from home, a thousand miles away from my nearest loved ones in Mombasa, about to go through with a ritual that I had only ever read about or heard about but never actually seen. There was no one here that I knew to witness this, only God alone, and I didn’t even know if I really truly understood what I was about to do here. I was frightened that I might be doing something foolish, putting myself into the camp of the simple-minded. After all, I’d had a personal revelation of God and a lived experience of repentance, but I was also scientifically literate, highly educated, worldly and traveled. I was not a superstitious person, not a frontier whacko (though I know plenty of them), not susceptible to medieval or antiquated thinking, but I felt I saw a value in this reason-defying procedure. I desired to move beyond who I was and what I’d understood up to this point. I was chief amongst sinners, but I wished to humble myself to things greater than myself, to my Creator and His plan. I wanted to follow in the footsteps of Haile Selassie I, to place my feet on the pathways of faith, and to see what I could become on the other side.

It was with this turmoil within that I removed my shoes and entered the church, escorted by Deacon Simeneh (my Godfather) into the basement. The narrow staircase descended, turned, descended further, and opened upon a large stone room. In the center of the room was a massive tiled baptismal fount, around which circumambulated several priests and deacons in elaborate gilded robes, with crowns, ornate umbrellas, censers issuing smoke, Bibles, and a flaming taper. As they blessed the waters of baptism, Deacon Simeneh and I took our seats amongst the families of 6 newborn infants, boys of 40 days and girls of 80 days, all asleep in their parents arms or baby-carriers at this point. I was to be the 7th. I felt so strange and out of place, the only “white” face in the place, and the only grown adult here to be baptized, the only one who didn’t understand the words of the language of the chants and readings.

Throughout the ceremony, the Bible was read aloud several times. Deacon Simeneh helped me out by opening a Bible app on his cell phone and giving it to me to read along in English. These were the verses pertaining to baptism: the gospel stories of Jesus Christ’s baptism at the hands of St. John the Baptist, the command he gave his apostles to go into the world baptizing in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, and the passages from St. Paul in his epistles, explaining the spiritual significance of Baptism. I knew these verses. They had all been part of the evidence that had led me here, things referenced in the teachings and public interviews of Haile Selassie I, and bandied about by the Rastafari community, with differing interpretations, but explained clearly in the doctrinal books of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and in the pamphlets and materials of the other Apostolic churches I had encountered. Now they took on a new importance. The things I had read about were actually happening to me now. I was about to put off the old man of sin and take on the new man.

As each of the infants was roused one at a time, stripped of their coverings, and immersed naked into the icy-cold baptismal water, they screamed and cried with all their souls, exactly in the way of a child emerging from the womb, which I had witnessed at the births of my two sons. At that point I began to feel like a fake or a phony, like there was no way I was gonna cry that same way or have that same experience of emotion, that same emptying-out. And then it was my turn, the 7th infant. I was led over to a curtained shower stall in the corner, used for adult baptisms, so that I could remove my clothes inside of it without exposing myself to all the adults in the room. Doing so, I handed my clothes out, setting them on the floor, and set myself also on the cold stone floor to await my baptism. Three times the priest appeared, dumping buckets of icy holy water on top of my head. And I did it. I cried just like those little babies, my entire body wracked with painful emotion. I was doing it. I was dying to whatever it was I had been before, dying to my evil ways, dying to my need for certainty and control over the world, dying to whatever remaining arrogance thought that I could be or do who Christ was or what he had done. I surrendered myself to Him and to His plan. This was my first Sacrament.

Then I was handed a towel to dry myself, and I dressed, and emerged from behind the shower curtains, feeling completely emptied and in awe.

Now a new ceremony commenced.

After further prayers and readings, a cross-shaped quartzite vial of holy anointing oil appeared. Each of the infants was anointed on 7 places all over their body, sealed with the sign of the cross, and given a new name–whispered into their parents’ ears. Then I was likewise sealed, anointed, and a new name was whispered into my ear, “Amha Selassie”. This name, meaning “Gift of the Holy Trinity,” is significant as the regnal name of the Ethiopian emperor-in-exile following Haile Selassie I’s deposition, when his son Asfa Wossen took the name Amha Selassie I upon claiming the throne in exile in the 1990s. This son was widely regarded as unworthy and disloyal, but maybe I could be a new Amha Selassie and be found worthy. This was my second Sacrament.

Following the anointing, I was handed a baptismal certificate and given a pen to write my full name, my parents’ names, places of birth and residence, birthdate, today’s date, and the new name that I was given. I was reminded at this point of the Nyahbinghi chant that I had repeated so many times at Rastafari gatherings over the years, “wrap my finger ’round JAH golden pen, and write my name up there.”

“Wrap my finger ’round JAH golden pen, JAH golden pen, JAH golden pen. Wrap my finger ’round JAH golden pen, and write my name up there.” – Nyahbinghi Chant

Then we were ushered upstairs into the packed Cathedral and brought to the front of the line of those awaiting communion as the Qedassie ceremony came to its climax. The room looked so different now than it had in the daytime, now illuminated by chandeliers and every square-inch packed with white-clothed worshippers. A platoon of elaborately robed deacons, priests, and bishops stood at the front, where the resplendent Patriarch of the Ethiopian Church stood with the sacred altar containing the flesh of Christ. Each of the 6 infants was carried forward, given their little piece of the Lord’s flesh and their spoonful of the holy blood. Then, it was my turn. A TV crew appeared with cameras in my face as the Patriarch, Abuna Matthias, placed the holy eucharist in my mouth. A deacon held a spoon for me to sip, and then I walked dazed down the aisle, Simeneh guiding me to a place to sit. This was my third Sacrament.

The rest of the story is anti-climactic. We stayed for prayers and hymns, I found my way home to the guesthouse, and I slept most of the day. I bought some souvenirs for my family in the afternoon. I woke up on Monday morning with traveler’s diarrhea, which often happens when visiting a new country, then had to deal with all the matters of packing bags, transport, airport security and check-in lines, passport control, boarding and all that while also sick and running to the bathroom as often as possible. I told you it was anti-climactic. But, I made it home to my family in Mombasa, and eventually home to the USA. I found a church to attend regularly and have been growing steadfastly in the faith and in the fulfillment of the Christian Life that Haile Selassie I taught me about, another phase of my journey.

The Appeal to Rastafari of May, 2024

I am writing this account of the events of April, 2018 from the vantage point of 6 years later, as it is now June, 2024. This is because something occurred in May, 2024 that compelled me to act.

I am active in several Rastafari groups. Aside from the community here in the Seattle area, I am also a founder of the Rastafari Community Development Office of Mombasa, an active member of the Association of Rastafari Creatives, and the producer of audio books containing the testimonies of Rastafari Ancients for Wisemind Publications. I am networked with Rastafari globally through numerous personal connections, phone and email, as well as social media apps such as Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Telegram, and Viber. A lot comes across my vision in a given day.

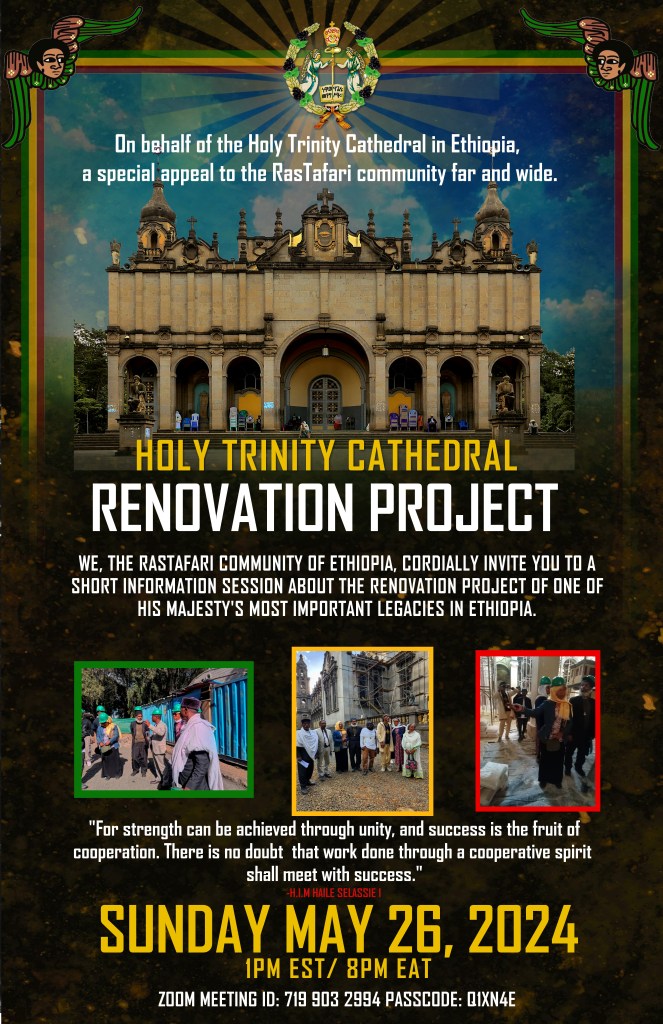

Recently, in May, the announcement of a Zoom meeting for the Rastafari community in regards to Holy Trinity Cathedral appeared in several of my groups. I was teaching Sunday School at St. Maryam & St. Arseima church in Lynnwood at the time of the meeting, but after church I logged on to catch the tail end. Afterwards, I contacted the meeting’s organizers and volunteered my services. I have since been helping in the crafting of press releases and engaged in outreach for this new campaign.

What is this new campaign, you may ask?

The Holy Trinity Cathedral where I was baptized in Addis Ababa is undergoing major renovations. This important church, which was constructed by Haile Selassie I after World War 2, has seen 8 decades of constant service, but has not been repaired. The full cost of these repairs, now underway, is USD$ 3.2 million, of which only $2 million has been raised. The church administrators, therefore, have decided to make an appeal to the Rastafari Community globally to assist in raising these funds. Rastafari brought me to church, and this is the church he brought me to, so I felt it was significant that I pitch in.

It is, after all, a question of legacy. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church has a legacy to uphold, that of Emperor Haile Selassie I, who led a global war to defend his nation and it’s religion from the absolute genocide and erasure sought by Fascist invaders, then led his Church out of dependence on the Coptic Church of Egypt and into the autocephaly of having their own Patriarch, having built 1500-2100 (the number is variously reported) church buildings using his own finances. It is also the work of the Emperor, as Head of the Church, that sent bishops into the west, establishing churches throughout the Americas and Caribbean, and baptizing thousands of people from the African diaspora there, including a claimed 50,000 dreadlocked Rastafari between the years 1970 and 1980 baptized by Abuna Yesehaq (Apostle to the West) and his mission. It is also a question of legacy for the members of the Rastafari movement, who have named themselves after this King (formerly known as Ras Tafari Makonen), and themselves represent His Majesty’s legacy. If the Rastafari movement does not uphold the legacy of Haile Selassie I, then what is the point? This legacy includes those many churches, as well as schools, hospitals, and other institutions around the world.

Fundraising committee chairperson Priest Beruk Wallelgn had this to say,

“Your Excellency Rastafarians, As we pen these words to you we are mindful of the profound connection you hold with Emperor Haile Selassie, a revered leader who remains etched in the annals of our hearts and history. Your steadfast dedication to the legacy of the Emperor leads us to believe that your support and guidance could prove instrumental in the successful completion of the renovation of the Holy Trinity Cathedral.”

This appeal for support was issued by the Church leaders to the members of the Rastafari community in Addis Ababa. In response, they sent delegates to tour the church grounds, and issued their own report. Now the Rastafari Family Centre is campaigning globally to bring this fundraising campaign to the attention of Rastafari faithful around the world.

If you are interested in contributing, you may contact Janelle Hoilett, Community Outreach Officer for the RasTafari Family Centre, for more information. +251-946-872-655 or rastafarifamilycentre@gmail.com

You may also use the following fundraising links to make a contribution directly to the Cathedral renovation fund:

http://www.gofundme.com/f/wkn6c4

http://www.wegenfund.com/causes/holytrinity

http://www.eotc-htc.org (using the ‘donate’ icon)