They say a picture is worth a thousand words. Well, I took 1000 pictures on this trip, so I guess that to tell this story I’d need a MILLION words. And that’s not even counting all the things that happened between the photos. I simply cannot do that; write as I may, I can’t do this story justice. I have been home for 21 days and haven’t yet found the time to write something short and basic about this trip. So, rather than a series of dully detailed blogs, I think a quick summary will have to do. (I’ve also included 80 of my favorite photos.)

To briefly sum up this trip: We visited 5 Ethiopian Orthodox Churches, 3 basic schools run by the church, 3 Nyabinghi Tabernacles, Bob Marley’s birthplace & mausoleum, the Bob Marley Museum, Kingston Night Market, Kingston Dub Club, the Haile Selassie I High School, and the Debre Zeit Orthodox Rastafarian community. We met many Ethiopian Orthodox priests & deacons, as well as Rastafari ancients and elders, influential community members, and Reggae artists. I introduced a great-granddaughter of Haile Selassie I to a granddaughter of Bob Marley, and on the last day we got a surprise ride to the airport from Reggae superstar Sizzla Kalonji. Quite the trip.

Day 1 – Monday, February 24th, 2025

This was a busy work day for me, but in the afternoon I packed my bags and drove south to pickup my traveling companions. These were a group of 3 Ethiopians, members of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church here in the Seattle, Washington, area who love His Majesty Emperor Haile Selassie I and believe in the Emperor’s legacy. Two of them, Yoseph & Titi, are the godparents of my sons, Javan (Sahle Selassie) and Nathan (Habte Selassie). These two are descendants of Ethiopian royalty and nobility (Titi is a great-granddaughter of Haile Selassie I and Empress Menen) and they have been asking me for about 4 or 5 years to take them to Jamaica to meet the Rastafari and see the state of the Church there. The third, Teddy, is a Rastaman originally from Addis who was inspired by the interview I did with Father Haile Malekot in Ocho Rios two years ago and was motivated to join us for the trip.

There’s not much to tell about this day. We drove to the airport, where we caught an overnight flight to Miami. A powerful storm raged quite dramatically during this entire period, delaying my drive South on I-5 with buffeting winds sweeping heavy rain sideways across the road and obstructing vision. The power was out all over Teddy’s neighborhood of Fremont, and thunder and lightning put on a show in the sky. The plane was rocked by heavy turbulence, but we continued to pray. Our spirits were buoyed by joyful excitement and anticipation, and we made it into the air safely. Yoseph and Teddy had never met before, but they discovered that they’d both grown up in the same neighborhood of Addis Ababa and knew dozens (maybe hundreds?) of the same people, including many who people who now live in Seattle. They were instant brothers.

Day 2 – Tuesday, February 25th, 2025

After changing planes in Miami and a short flight south through the Caribbean, we arrived in Kingston around noontime. It was not an easy airport to get out of, with all the paperwork and questions and various check points for this or that. We were being met there by a member of the church in New Jersey who was in country at the same time and said he’d give us a ride. I also called a bredren of mine who lives nearby in Harborview, and I’m glad I did, because the first vehicle was definitely not big enough for all of us and our bags. They waited a long time for us to get out of the airport, and in the meantime offered a ride to another passenger who’d gotten off the same plane as us.

On the way out, I say Reggae singer Chronixx and gave him a head nod, but I didn’t have time to talk and he didn’t look like he was in the talking mood anyway. After we’d loaded our bags and were driving off, we saw him being pulled over by the police. I said, “I’m pretty sure that was Chronixx,” but no one believed me. I later found out it was truly him, but that’s not really relevant to our story right now.

Our drivers took us to the nearby Caribbean Maritime University, where our host–an Ethiopian Orthodox Priest called Kes Haile Mikael, also known as Ibby Lion–operates an Ital kitchen on the campus. We enjoyed a fully plant-based meal of Caribbean delights (like Ackee, my favorite) eaten out of calabash bowls, and everyone got a chance to meet one another. This was my first time linking in person with Iyah Gift, the bredren from Harborview, who I’d met virtually through the ARC group (Association of Rastafari Creatives) that we’ve both been active with for several years. He was one of the summer school teachers who’d worked with my sons last year, and it was a blessing to make the link in person. We also got to know our temporary friend from New Zealand (the girl from the plane who’d hitched a ride with us) before she headed off to her guesthouse.

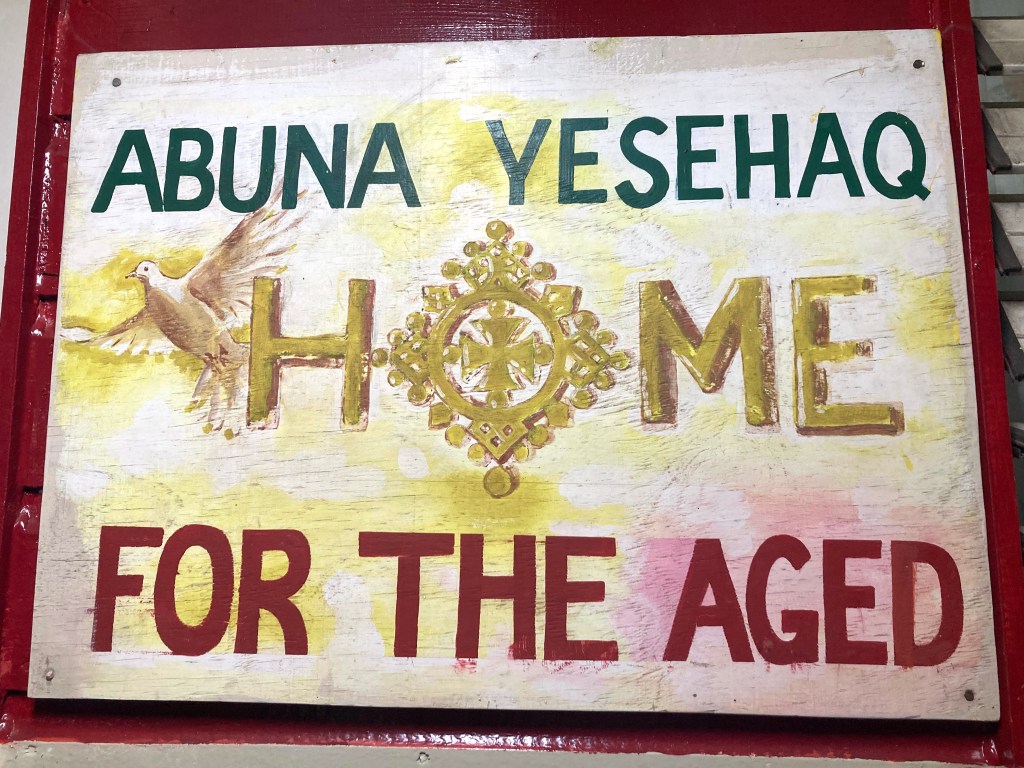

From there, we dropped our baggage at Iyah Gift’s house, where I learned to my surprise that we’d be staying the night (turns out he and the priest were also linked). Then we climbed into the priest’s van for a trip into Kingston. After picking up his daughter Sitota from school, we made a quick visit to the Holy Trinity Cathedral and Abuna Yesehaq Home for the Aged. There we met the monk/priest (Qommos) and administrator of the island, Abba Samuel, who happens to be friends with the current qommos at our home church, Abba Ephraim. We met several ancient Rasta people there, including Emmanuel who watches the gate, Tekle Haimanot, and Hanna Maryam. It was Hanna Maryam’s 90th birthday on the day we arrived, and she was touched to share it with visitors from Ethiopia.

After that, we headed to the Kingston Night Market, where we sampled fresh fruits and Ital dishes, browsed local arts & crafts, and enjoyed live musical performances from some of Kingston’s up-and-coming talent. I got to meet another bredren I knew from the ARC group, I-Nation, who sells books on Rastafari and African subjects. I picked up a couple small-format books of Haile Selassie I’s speeches published by Frontline Books. I also met Roots Reggae legend Fred Locks, whose ex-wife is an acquaintance of mine through the IDOR group (International Development of Rastafari). There was a Nyahbinghi elder from Japan, selling Ital Caribbean-Japanese fusion food and smoking chalice. I also reasoned with a Bobo dread who was very supportive of our mission with the Orthodox Church on the island. Teddy spoke with dub poet Mutabaruka, and at one point Teddy and I walked up the street to poke our heads in at 12 Tribes HQ, where they were holding a concert.

We returned to Iyah Gift’s house in Harbor View and stayed up talking into the early hours of the morning.

Day 3 – Wednesday, February 26th, 2025

I guess I thought I was on a “normal” vacation, so I got up and went for a run, did a little workout, took a shower, and ate breakfast–all things that I would not have the opportunity to do on many of the days of this trip. Kes Haile Mikael picked us up around 11am for what turned out to be a very long day’s road trip around the East end of the island.

Our first stop was the St. Tekle Haimanot Basic School in Bull Bay. We met the principal and all of the sweet little children, took a few photos, and then were on our way. Somewhere along the side of the highway we found a waterfall, where Teddy and Yoseph decided to bathe while Titi, Ibby, and I spoke to an Irish Moss diver who was drying his sea moss on the roadside in the sun. Then we were up into the hills to visit another Jamaican Priest from the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.

From there east, the roads were in really bad shape and under active construction. We were happy to see the scenery (Jamaica is absolutely beautiful), but even happier to see the little Ital cafe on the side of the road, where Kesis (sometimes we just call our priests “Kesis”) took us for lunch. There I saw one of the Jahug issues (a legendary small-format Rastafari magazine from the UK) hanging on the wall and I snapped a photo to send to the publisher, a Tewahedo Rastafari matriarch living in Shashemane, Ethiopia named Askale Selassie. I also took this opportunity to make a phone call to England and update one of my friends who is a Deacon there at St. Mary of Zion, discovering that he was also connected to Kes Haile Mikael (something that happened to the two of us often). It truly is a small world.

The trip from there was bumpy and dusty and slow, but we eventually made it around the end of the island to Portland, where we arrived at St. Gabriel’s Church late in the evening of St. Gabriel’s Day. Driving up the narrow, windy road with a sheer cliff at our right and a river down below at our left, both Yoseph and I remarked that this reminded us of Debra Damo, the mountain monastery founded by Abune Aregawi in Ethiopia. When we got inside the church, we found an icon of Abune Aregawi there.

Saint Gabriel’s is a very special community built around a small church in the jungle. We got the story from the barefoot deacon, Wolde Gabriel. HIs family, who owned the property, had actually begun by worshipping in their home, having the priest visit to perform liturgy for them. The deacon’s father, a Rastaman, had later gifted a piece of this land to the Church and built this house for Saint Gabriel. His son is still living there along with his elderly mother (in her 90s), wife, children, and another elderly Rastaman turned priest. It was my impression that there are even more Orthodox people living in the vicinity.

We left there to find our lodgings, a guesthouse owned by Kes Haile Mikael’s aunt. To our surprise, it was just across the highway from the road that leads to the church, and we were settled into our rooms in minutes. Then the priest invited us to go up the road to the memorial of a woman named Mama Fyah, who had passed away 9 nights before. We’d learned that day on the road trip about the peculiar funerary customs of Jamaicans, which–as Kesis explained to us–consist of a total 15 days of various celebrations or events, such as the “Nine Night”, “Grave Digging”, and the funeral itself. We passed one of these grave diggings on the road and it was a large affair. We also passed a graveyard resplendent with full-sized cardboard cutouts of the deceased, ala March Madness during the COVID pandemic. Kesis explained that the Orthodox Church does not condone all of these customs, but this is what is common.

Mama Fyah is a very interesting woman, and very important to the Rastafari community. I never had the chance to meet her in this life, but I have heard a lot about her, and her influence is felt far and wide. She was born into a Rastafari family and baptized into the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Her grandfather was Solomon Wolfe, one of the pioneer settlers of Shashemane in Ethiopia. She was known as a Nyahbinghi matriarch, and was the first woman to open a Nyahbinghi tabernacle and hold Ises. She instituted the Nyahbinghi celebration for Battle of Adwa Day, which occurred the following weekend while we were in other parts of the island. We were privileged to meet Papa Fyah, have a little Ital sip from his kitchen, and witness both the Kumina drumming of the Maroons and the Nyahbinghi drumming of the Rastafari at her memorial ceremony.

Day 4 – Thursday, February 27th, 2025

We were up early in the morning to drive to Ocho Rios, where we dropped off our bags of gifts at the church, met our church brother from New Jersey who’d picked us up at the airport (Kinfe Mikael), and met another friend of his, the Ethiopian historian Mulugeta Haile, who happens to be living in Jamaica currently while he works on a book about Dr. Malaku Bayen, founder of THE ETHIOPIAN WORLD FEDERATION, INCORPORATED.

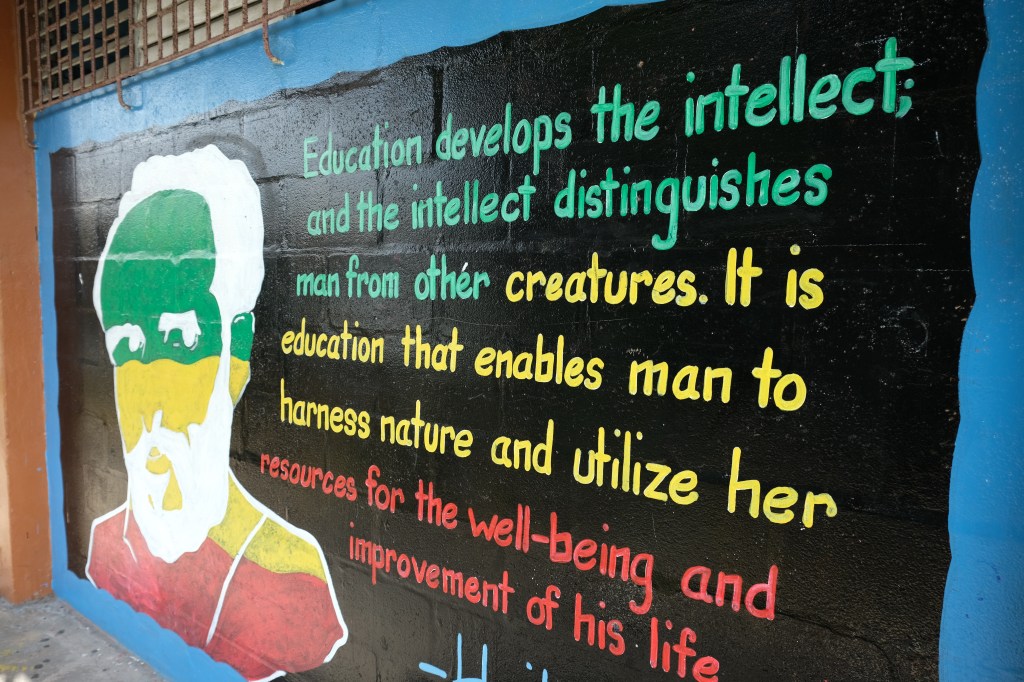

From there, we drove to Kingston on the nice, new toll road. This was by far the smoothest and fastest drive on the whole island. I recommend taking this way if you need to travel north/south. We were headed to a Black History Month event at Haile Selassie High School, the school His Imperial Majesty gifted to the government of Jamaica (presenting gold bars, no less) during the state visit of 1966.

We arrived in the middle of a program of speeches and musical performances for the students. There I met in-person for the first time Queen Mother M.O.S.E.S. (those are the initials of her 5 names). We have already been acquainted for several years through the IDOR group and ARC, and she instantly recognized me with a big, motherly hug. She was amongst many other notables from the Rastafari community attending the event. The highlight by far was History Man, who got the students’ attention with a series of history-lesson songs and raps, using cleverly arranged Q&As and a cash prize handed out to the students paying the closest attention whenever they were ready at the right time with the correct answers. I think this was a brilliant teaching technique, perfectly tailored to the Jamaican youths, Rastafari culture, and the day’s Black History topic. Another highlight was Reggae singer Mikey General, who is also a member of our Church.

After the program had ended and the students were dismissed to go home, all of the VIPs (including us), were invited upstairs to one of the classrooms for a presentation by the new principal, Mrs. Anniona Jones. SHE was, by far, the highlight of the day. In this room full of entertainers, academics, and influencers, Mrs. Jones went on to capture everyone’s attention, interest, and compassion with a powerful series of speeches, first in the decaying classroom, then in a newly renovated library, then with a tour around the grounds, finally ending at the dedication plaque, which describes the history of the school. She relayed a story that when she was interviewed for the job, she told the committee, “I don’t want a job, I hate them. I want to follow my purpose. You can’t fire me from my purpose!” That was the quote that stuck with us. She left us all eager to help, excited by the possibilities, and ready to follow her vision for the future of the school.

The school itself is situated in an impoverished and underdeveloped neighborhood, bordered by crime-ridden housing blocks that are often at war with one another. Students have to use shortcuts and holes in the wall to travel to and from safely. Despite His Majesty’s reported gift of gold bars to build an institute of higher education with dormitories attached, the Government of Jamaica built a high school that feels more like a prison, with barbed wire across the walls and along the roofs. The entire annual budget for the school–including teachers, administrative staff, maintenance personnel, cooks, bills, and supplies–is less than what one teacher in the USA makes for their salary in a year. The vision of the new principal, Mrs. Jones, involves concerned community members, impassioned supporters of His Majesty, and other volunteers, coming into the school to pitch in with materials, time, skills, and other resources worth far more than money. I told her that–between the Rastafari community, the Pan-African community, and the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church–she had all the resources she would ever need.

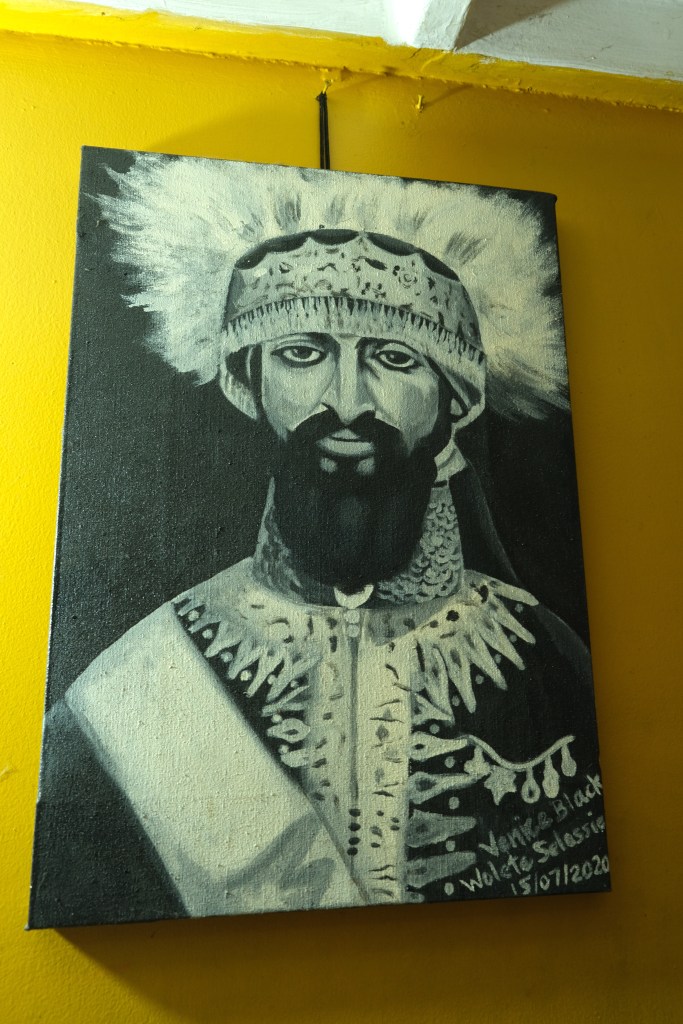

From there we traveled to meet another Ethiopian Orthodox Priest in Kingson, Kes Matewos. The inside of his house was decorated like an Ethiopian church, with icons of the Holy Trinity, Virgin Mary, and the saints adorning the walls, while a powerful painting of Haile Selassie I beheld all. There we ate and talked and got to know the priest, his delightful family, and one other. There were a lot of us now, as the group from Ocho Rios had traveled here to join us, including Kinfe Mikael, his young houseboy Ricardo, and the historian Mulugeta. Count the four of us, Kes Haile Mikael, Kes Matweos and his family, and we were 12 in all. It was the typical Ethiopian/African culture thing of “pray, party, eat”, and it was so joyful that I completely lost track of time.

There was another event that evening that I’d been meaning to attend, the Independent Film Series at Bob Marley Museum, hosted by Sister Donisha Prendergast (another friend of mine from the ARC group). I was meant to be meeting Brother Kush, another ARC Filmmaker there as well. By the time I noticed the time, we had missed half the night’s program, but 4 of us headed up there anyways, while the group from Ocho Rios took Teddy home with them. Donisha was pleased to see me when we arrived and she ushered us quickly into a screening which had just begun. It was a documentary film about Reggae legend Peter Tosh. As we entered and seated ourselves in the back row, someone turned around and said, “you’re late.”

We enjoyed the film all the way through the credits, then exited into the lobby/gallery space to meet some of the other people there. We met the filmmaker, as well as a young lady named Kadiya, who I recognized as the sister of Reggae singer Kelissa, but didn’t realize she was also the sibling of Kamila, Kimani, and Keznamdi, who are all well-known in their own rights as models, chefs, doctors, musicians, etc. Putting the pieces together later, I realized that I’d actually watched a documentary episode about their family’s residence in Tanzania on a plane ride to Africa many years ago, and met one of their brother’s school friends while we were staying in Oyster Bay, Tanzania in 2022 (he asked me if I’d ever heard of this Reggae artist, Keznamdi, and I said, “Of course!”).

Then came the part where I got to introduce a great-granddaughter of Haile Selassie I (Titi) to a granddaughter of Bob Marley (Donisha). This is when Kes Haile Mikael came into the room and said to Donisha, “this is our brother Nic, Amha Selassie, and he’s kind of the mastermind of this whole visit.” She said, “yeah, me know him man!” It was a thing that kept happening for the whole trip, when the priest would try to introduce me to someone and then figure out that we already knew each other, or I would ask to link with a certain person and he would already know where they were going to be. It’s just a small world when you’re resonating on the same frequencies.

Day 5 – Friday, February 28th, 2025

We stayed the night at Kes Matewos’s house, and then the next morning as we were waiting for our ride, got to know his wife Jessie. She had a Binghi drum sitting there (the Burro Akette) and I asked if I could play it. I began a chant that I’d learned a couple years back after my prior visit to Jamaica. It was given to me on a piece of photocopied paper when I went to St. Mary of Zion in Ocho Rios. Then, I’d asked Brother Icah in California (who used to drum with Ras Mikael of the Sons of Negus) to teach me the tune. So, I thought I knew what I was doing. But, when I started chanting, Jessie said, “No, that’s all wrong. That’s not how it goes. My grandfather wrote that chant!”

It turns out that her grandfather had been a very important man in the Ethiopian Church in Jamaica, the man who had built the altar for Holy Trinity Church after receiving it in a vision, had written the book of Nyahbinghi-chants-turned-church-hymns that are still used in the Jamaican Orthodox Church today, and had raised multiple generations of his family within the Church.

Jessie relayed to us a story of how her and her sisters had been recorded performing some of these chants for Sir Coxsone Dodd, who had then ripped them off and mixed the recordings with some other music so it was no longer a faithful reproduction. Other than that, apparently, the full book of hymns has not been published, nor the tunes recorded. I intend one day to help make that happen.

Then Kinfe Mikael arrived, with Mulugeta, to drive us out West so we could visit another church in Savanna La Mar. Now we were all packed together, with our bags, in a much smaller vehicle than the Priest’s van, and it was uncomfortable. The roads were much better though, and we made the time enjoyable by telling stories.

Somewhere along the way to Savanna La Mar, in the area called Westmoreland, we passed the home of Peter Tosh. Kinfe Mikael told us there used to be another church near there, but it was no longer operating. Then we saw it, St. Raphael’s Church, there by the side of the road. We parked the car and got out to investigate. It was certainly abandoned, in poor shape, with holes in the walls, a broken door, and evidence of goats and other animals living inside. The pews were overturned, the altar neglected, and a single lonely bass drum sat in the corner (with a little lizard seated on top). We prayed over the forsaken church and questioned why the Lord had allowed it to be this way. I think it was so we could find it and feel this way, and then do something about it.

A bit further up the road, we stopped to ask for directions. But, the man we stopped to ask was mentally disabled, begging for money to, “buy Pepsi”, and he was not helpful. While we negotiated his request and dug in our pockets for spare change, another man came up to the window. He asked us if we were with the Ethiopian Orthodox Church (but, who knows how he surmised that?) and we told him we were. We noticed that he wore an intricate Ethiopian Meskel (cross) around his neck, and he told us, “I was baptized and I never left the faith”. In fact, he had formerly been a resident at Debre Zeit (the Orthodox Rastafari community in Kingston) and as he and Kinfe Mikael spoke, they realized that they’d known each other many years ago. But, he’d been shot in Kingston and had fled to this area maybe 20 years back. We told him to keep an eye on St. Raphael’s and we’d send people to check on him. He promised that he would.

Then we were on to Savanna La Mar, and this part of the drive wasn’t so memorable. The roads here were good and we had good conversations, so the time passed easily. We got a bit lost, but figured it out, and eventually arrived at St. Mark’s Church.

This was easily the nicest church that we had found on our trip, and it was attended by two priests who had been best friends their entire lives, had found the church together in the 1970s, and both become deacons before entering the priesthood. We prayed, took photos, made some short video interviews with the priests, and had a bit of local fresh fruits.

By that point, we were all hungry for a proper meal, and we still had a long ways to drive before lodging for the night in Montego Bay to the North. We’d heard about an Ethiopian restaurant in Negril, so we headed there. Our Ethiopian guests had been craving injera. It was exceedingly expensive (a plate of food cost about 3 times what it would for a comparable plate in Seattle), the service was slow, and the injera was two weeks old and getting stale, but it was in the most beautiful setting–as the sun settled down in the west–the food was tasty, and the conversation was interesting. So, in all it was a pleasant dinner. We even saw a mongoose drag a dead rat into the bushes to feed his family, before returning to the hunt.

After that was a long drive up the coast in the dark to Montego Bay. Story time. At some point, Mulugeta said the unforgettable line, “Amha,” (they all called me by my Ethiopian name there), “I’m going to need a special course to learn how to be your friend.” That at least told me that he was interested in being my friend, and that my unusual life’s stories were being appreciated. One thing about this trip is that every step of the way I felt like I could be myself without apology. I owned my life, its unusual idiosyncrasies, its ups and downs, ignorance, errors, and path of repentance. And I never felt like I was being judged, gaslighted, or gate-keepered by anyone there. It was just pure love all the time.

We arrived in Montego Bay quite late at night, to the home of Kinfe Mikael’s sister, Fanaye (another one I’d met already in one of the ARC virtual meetings), whose Rastafari TV website and social media channels are probably the largest in the world in terms of audience size. She’s rented a regal home there in the Coral Gardens neighborhood. This place is infamously known for the Coral Gardens Atrocity of 1963, when the government of Jamaica attempted a genocide on the Rastafari in the island. Now Rastafari are rising from this martyrdom.

She calls the home “Villa Lalibela” and plans to use it for retreats and home stays in the future. We were all caught up in stimulating conversations late into the night with herself and her groundskeeper, an herbalist named Jah Word (both of whom we’d met at Haile Selassie High School the day before).

Day 6 – Saturday, March 1st, 2025

We woke up on Saturday to another very beautiful morning, but there was a problem that I was quickly made aware of. Our ride for the day, which the priest had taken efforts to arrange, had fallen through. Now we were stuck temporarily at Villa Lalibela until we could figure something else out. It wasn’t a bad place to be stranded. Our hostess made us an excellent breakfast of Ital stew, and we sampled some of the fresh juices and herbs tonics they produce.

All of these things set us back bit by bit, and by the time we reached Pitfour Nyahbinghi, we were already maybe 60-90 minutes behind schedule. Is that really important to the story? Well, it seemed to happen every day like that, and it verified the same rule that I always try to follow in Africa–or in Hawaii for that matter–don’t try to do more than one thing in a day. Of course, on this trip we were doing many more things than one in a day, and that meant some things were not going to work out. The days would be long, we wouldn’t eat, drink, or sleep very much, and we’d be quite tired. That played into some of the things that happened later in the day.

At Pitfour Nyahbinghi, our ride left us to go to the airport, and we met Ras Flako Tafari, an elder within the Nyahbinghi Order. This is a man I have known for a very long time (since about 2008, I think). Ras Flako often travels to Seattle for Groundations and has been helpful in organizing our Rastafari community progressively over the decades. We keep a regular correspondence and I have recently been pitching in with one of his organizations, Wisemind Publications, to produce audio books and do a little proofreading. He showed us across the Binghi grounds and up the hill to a little house currently under construction for Bongo Cecil.

Bongo Cecil is an ancient Rastaman in his 90th year of life. Born in 1935, he is a member of THE ETHIOPIAN WORLD FEDERATION, INCORPORATED, the Nyahbinghi Order, and the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. He owns little more than the clothing upon his back and has led a very difficult life, but is still full of love and happiness. He lives in a small, partially-completed house of cement bricks and metal sheets, with ongoing construction being funded by donations to the Word Sound Power Collective administered by Ras Flako and also Ras Scott here in Seattle.

It was very important for our Ethiopian guests to meet Bongo Cecil and see the conditions that he is living in, so that they can understand the life path of the Rastafari ancients and know where their desire for repatriation to Ethiopia comes from. Bongo Cecil, for one, did not grow up with his own family, but was raised by relatives who worked him as unpaid farm labor, and then persecuted him for being a Rastafari. He told me that his only desire for his entire life has been to return to Africa, his motherland. He said that His Majesty first sent THE ETHIOPIAN WORLD FEDERATION, INCORPORATED to bring them home, but that the “forward men” (leadership) messed it up. And then, a second time, His Majesty sent The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church to bring them home, but the same thing happened again. With tears in his eyes, he said to me, “my only desire is to go home to my Mama, to Ethiopia.” Before we left, I told him, “I don’t know how we will do it, but we will help you reach Ethiopia before you hit 100.”

Now we were stranded there in Pitfour. Kinfe Mikael, before he left, had called for a private van and drive to pick us up and drive us for the rest of the day, but the van hadn’t shown up. We managed to get them on the phone and they were lost. So we departed from Bongo Cecil, bidding farewell to Bongo Joe and Bongo Gredo (keepers of the grounds there), and grabbed a taxi into town with Ras Flako. There we met our new driver, Robert, and our friend Ricardo, the young man who takes care of Kinfe Mikael’s house. We were well behind schedule now and needed to hit the road quickly to make it to our next destination before closing time.

Next on the agenda was Nine Mile, the place way up in the hills of Saint Anne Parish where Bob Marley was born and later buried. There is also an Ethiopian Orthodox chapel there that we wanted to see with our own eyes. So we hit the road on another long day of road tripping. More story time.

When I told my story of being baptized in Ethiopia during Fasika (Easter) of 2018 (2010 E.C.), I got a strong reaction from the historian Mulugeta. He clapped his hands slowly and proclaimed, “8 out of 10,” which coming from someone like him is like an 11 from anybody else. He told me at this time, “This, Amha, is what you should do. Your stories, your real life, is far more interesting than your boring ideas for documentaries.” I’m still mulling that one over.

We arrived at Nine Mile before dark, but not much before. The place was empty, all the customers were gone, and there was only one tour guide left. He took us up to the gift shop to speak with the manager and we were soon given a full private tour. The base camp there is crowded with shops and restaurants, all of them closed when we visited. But, you can see how on a busy day in the height of tourist season, this place would be packed.

First on the tour was the small house that Bob Marley was born in, with a full explanation of the relationship between his parents and his early history. Then, we went into a small museum adjacent, with monuments to Bob’s biggest records and eventful tours. Outside there was a small stage and lots of gorgeous murals. I took many pictures here, but I think some of the settings on my camera had been bumped and none of them turned out good.

Then we walked up the steep hill to the family mausoleums. There at the top was the small house Bob had often lived in during his youth, with the single bed that he sings about (“we’ll share the shelter of my single bed”). There was also a little Orthodox chapel with a stunning icon of the Virgin Mary with Child painted onto the wall. We paused there for prayers. Next, we visited the tomb of Bob’s mother Cedella Booker, who shared the same birthday as Haile Selassie I and was largely responsible for Bob’s outlook on life, following Marcus Garvey, Haile Selassie I, and ending up in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. We saw the portraits of the two of Bob’s grandchildren who died young and are buried behind in a private family cemetery. Nearby, at the very highest point of the hill, was the mausoleum for the Honorable Robert Nesta Marley, O.M., who in his very short 36 years of life made an incredible impact on the world. There we saw many flowers and flags, pictures and mementos left by admirers and mourners over the years. I took a look at the view from up there and marveled at the sound coming from a sound system across the street. The tour guide told us that was the home of Bunny Wailer’s sister (who is also Bob’s sister), and that she keeps the loudest sound system in the entire island. It was a humble home with people coming and going casually, and the sound was pure roots Reggae.

Now we were back on the road and it was getting dark. We hadn’t eaten more than a few nuts and juices since breakfast and we were all quite tired (now 6 days into our epic journey). Then Ricardo began to panic that he couldn’t reach our bredren Teddy on the phone. I’d also been trying him without success all day. When we spoke to Kes Haile Mikael, we realized that Father Haile Malekot (the priest who we were all here to meet and who had inspired this trip through the interview I did with him two years ago) was also unreachable. We began to worry and to pray, but it was really just a kind of spiritual warfare, as we were all frayed and exhausted. In turns out both men were fine.

Shortly before arriving in Ocho Rios, we located Teddy, and another bredren we were communicating with located Father Haile Malekot. We stopped for dinner at Calabash Ital Restaurant (my favorite spot in Ocho Rios) and then up to Walkers Road where we would spend the night.

At Walker’s Road was a partially completed house owned by Kinfe Mikael, where Ricardo kept the grounds. There was a bed for me, but I wasn’t ready to sleep yet. I was still a little stressed out by the worries of earlier, and I decided to walk across the street to call my wife and talk with her. We had a good long talk as another Rastaman watched me pace back and forth. When I finished the call, I introduced myself to him and we sat down to reason. We were reasoning there for about two hours and everything the man said was pure love and blessings, straight Biblical, traditional Rastafari teachings. At one point, I explained that I was here with a group from the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, touring the churches in the island, and he asked me if we would bring him there with us in the morning. I began to explain basically everything about the church to him then, about how we arrive early in the morning and commence with prayers, standing for long hours in a communal chanting, then a eucharistic ceremony, then some hymn singing, and then a homily, followed by an Agape meal (love feast). As I explained how long and loving the Ethiopian church services are, he just patiently listened and nodded. Then, when I’d finished, he said, “Yes I know. I used to attend in Kingston, when Rita Marley was there.”

This is how I met Rasta Williams, a Nyahbinghi man, a 12 Tribes man, and an Ethiopian Orthodox man whose baptism name was “Yonas” or Jonah. He’d attended Holy Trinity Cathedral in Kingston in times past, but was now living near Ocho Rios and had not yet had the opportunity to reach St. Mary of Zion church just down the road from him. Sometimes all it takes is an introduction, or an invitation. It was about midnight now. We made an agreement to meet each other there at the corner at 6:30am and then I went off to bed.

Day 7 – Sunday, March 2nd, 2025

I awoke at 6am for an ice-cold bucket bath, then quickly dressed and packed my bags. By 6:30, I was outside at the street corner looking for Rasta Williams. I called him on the phone, but he didn’t answer, so I asked some of the neighbors, “Where does the Rastaman live?” They pointed me to a house behind the shops, and as I approached the house, my phone rang. It was Rasta Williams. He wasn’t quite ready yet, but he’d be there soon. Turns out this wasn’t the right house, but it must be another Rastaman who lives there.

I waited on the street for my companions and watched the taxi cabs stop at the corner. They were few and far between, and each one was so fully packed that they could barely fit one new passenger at a time from the small crowd who were gathered there waiting. Around 7am, my friends came out of the house with their bags, but I had no idea how we were going to find a taxi to take all 5 of us and still make it to the church on time. Rasta Williams had still not shown up.

So I got on the phone with Kes Haile Mikael, but he’d already passed this way earlier in the morning, coming from Kingston with Kes Matewos. He told me to wait there for the Evangelist, a man called Gebre Meskel, who was coming to pick up another brother, Libne Dengel, who lived in the area. A few minutes later, I saw Rasta Williams come racing down the hill on his bicycle, dressed up nicely for church. I gave him a hail up and he told me he just needed to park his bicycle safely behind the shops there.

Right then, a black SUV came by. This was Gebre Meskel, rolling down the window to tell us that he’d just need to pick up Libne Dengel and then he’d be right there to get us. As I walked across the street to meet Rasta Williams, I saw the black SUV pull up in front of the same house I’d walked up to earlier. It turns out the “other Rastaman” was Libne Dengel, who I’d met two years earlier on my prior visit to St. Mary of Zion. Since that time he has lost a leg and literally needed to be picked up by Gebre Meskel and carried to the vehicle. Then we picked up the rest of our group and soon the 7 of us were driving the road through Fern Gully to St. Mary’s in Ochi.

There is a classic film entitled The Third Man, released in the 1940s, and featuring an unforgettable performance by Orson Welles. It is widely considered to be one of the greatest films of all time, it won some academy awards, and it features stunning cinematography along with a memorable soundtrack. Even though Welles only appears in the final act of the film, and for less than 15 minutes, his character is the most memorable and significant of the film because, throughout the entire film, this is the man that people are talking about, the one they are looking for. He is mentioned so much in stories and recollections, that you feel like you know him already, like you’ve already met him long before you’ve actually seen him. For us, on this trip, that was Father Haile Malekot Dobson at St. Mary of Zion.

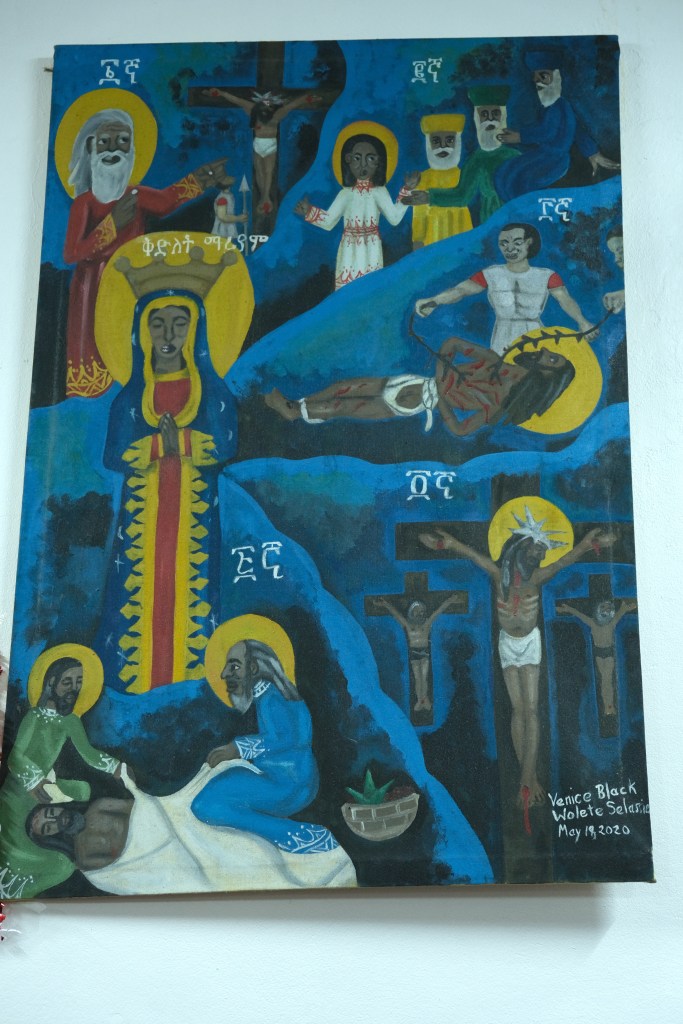

Father Malekot was the one we all came to see. He was the one who inspired this trip in many ways. The interview I filmed with him two years ago so moved this group of Ethiopians that they wanted to come and meet him in person and support his work. He helped me plan the trip, telling me who to speak to and what things would be important to do. The entire time we’d been in Jamaica, we’d been hearing stories about him. Now we’d finally have a chance to meet the man behind the name. When we arrived at Saint Mary’s, we proceeded directly to the small lean-to shack that they use to host church services while the cathedral is under construction. We draped ourselves in white prayer shawls (netela), removed our shoes, and said our prayers at the doorway before entering the church. Then the service began, about 3 long hours of standing and chanting as a group in a call and response fashion between the priests, deacons, and congregation. This is when we finally got to witness Father Haile Malekot, occasionally emerging from behind the curtains and iconostasis to bless the crowd with the sign of the cross as he led the ceremony along with several other priests, deacons, and two men in the role of Evangelists.

At home, this service is all done in a mixture of Ge’ez and Amharic, but here they included some English as well. I had no problem following along in my liturgy book, which included all three languages. Titi and Yoseph did the same thing they always do at our home church, standing strong for hours and lifting their voices loud, inspiring others to be strong in worship. There were many times this morning, as on this entire trip, that I came to involuntary tears of joy and repentance, especially during the prayers of preparation and acceptance of the Holy Communion.

After the Qidus Qorban (Holy Communion), there was singing of hymns in Amharic and English. Titi surprised the women by singing so clearly and loudly that some of them in the front rows had to turn around to see, who was this woman? After that, there was a sermon from the Evangelist Gebre Meskel, which was perhaps the finest sermon I have ever heard. Witnessing his enthusiasm and eloquence, the way he connected so well with his audience and their perspective as Rastafarians in the Church, I found it all to be deeply moving.

Then, to my surprise, Kes Haile Mikael came to the front to make a short speech about our little group of visitors, and invited me up to speak as well. I first presented my companions: Tewodrose (Teddy), the Ethiopian Rastaman who grew up on the streets of Addis Ababa and came to admire the Rastafari culture from Jamaica, adopting it as his own; Yemesrach (Titi), the great-grandaughter of Haile Selassie I, and her husband Yoseph, the nobleman, who—stripped of titles and inheritances by the revolutions in Ethiopia—have come to America to live as simple, regular people, whose love for Haile Selassie I and Empress Menen never fades, and whose love for Jamaicans compelled them to ask me to bring them here. I described for the benefit of our Jamaican family the humility and good character I have witnessed from these Ethiopians, as evidence of the good character of Haile Selassie I and Empress Menen themselves. Then I told them briefly of our mission here, how it came about, the things we had seen, learned, and accomplished, and what we intended to do in the future.

After these speeches, the service came to an end. There were prayers of benediction and then the entire group was dismissed to finally mix and mingle. A meal was served and we began the Ethio-Rastafari-Jamaican family reunion.

We had many gifts to present to Father Haile Malekot, including some priest’s robes and hats, decorative wooden crosses, incense, candles, and a bag of about 50 white netela for the worshippers there (most of them were given away before the day was done). Teddy had gifts of his own, including some very special crosses to give the two evangelists.

While our friends and family sat in little clusters here and there, talking, laughing, eating, or reading together, I busied myself with taking photographs and recording a series of video interviews. Documentation was an important part of our mission. Finally, I sat and broke my fast with the priests, and had the chance to meet in person some of the bredren that I’d only been introduced to through social media before.

We stayed there at the church with Father Haile Malekot and the others until about 4pm. Then we drove through Fern Gully, back to Walker’s Road, saying farewell to Ricardo, Libne Dengel, and Rasta Williams, before continuing on the country roads to Kingston.

This time I rode in the back with two young boys (priests’ sons). They wanted me to tell them stories about animals. So, I told them about giraffes and dogs, tigers, and orangutans, a good selection of my animal stories gathered from growing up in the Pacific Northwest, living in Thailand and Kenya, and traveling other parts of the world. It was clearly very exciting for a couple of young boys who’d read many books about these animals, but hadn’t yet had the chance to witness most of them in person.

We arrived in Kingston after dark, returning Kes Matewos and his family to their home, and dropping Kes Haile Mikael’s children at their home, before heading up Skyline Drive to visit a place called Kingston Dub Club. I told Kesis that I wanted to link with another bredren that night, Dutty Bookman, and he said, “he’ll be there.” Another synced-up moment where he and I were linked with the same people without even knowing it.

Kingston Dub Club was a joyful experience, a massive sound system at the top of the hill (near Bob Marley’s other mansion), complete with Ital kitchen. There we linked with some more Orthodox bredren, I got to meet Dutty Bookman face to face for the first time after many phone calls, emails, and such over the years, and we got to sit and reason with some 12 Tribes of Israel bredren from Germany. We were all quite tired though, and left a bit early in the program, headed across the city to Kesis’s house.

I was up telling the priest’s son animal stories again until about midnight that night when we finally all went to sleep.

Day 8 – Monday, March 3rd, 2025

We woke up very early, before 5am, so that we could drop Kesis’s kids off at school and get over to Holy Trinity on Maxfield Avenue in time for Kidane (an early morning prayer service). After the service and a reading from the lives of the saints, we stuck around to take photos and film interviews with some of the clergy. One of the major purposes of our trip to Jamaica was this photography and videography, to share with others in the global Ethiopian Orthodox diaspora and Rastafari “outernational” community the stories and experiences of the people and churches here in Jamaica.

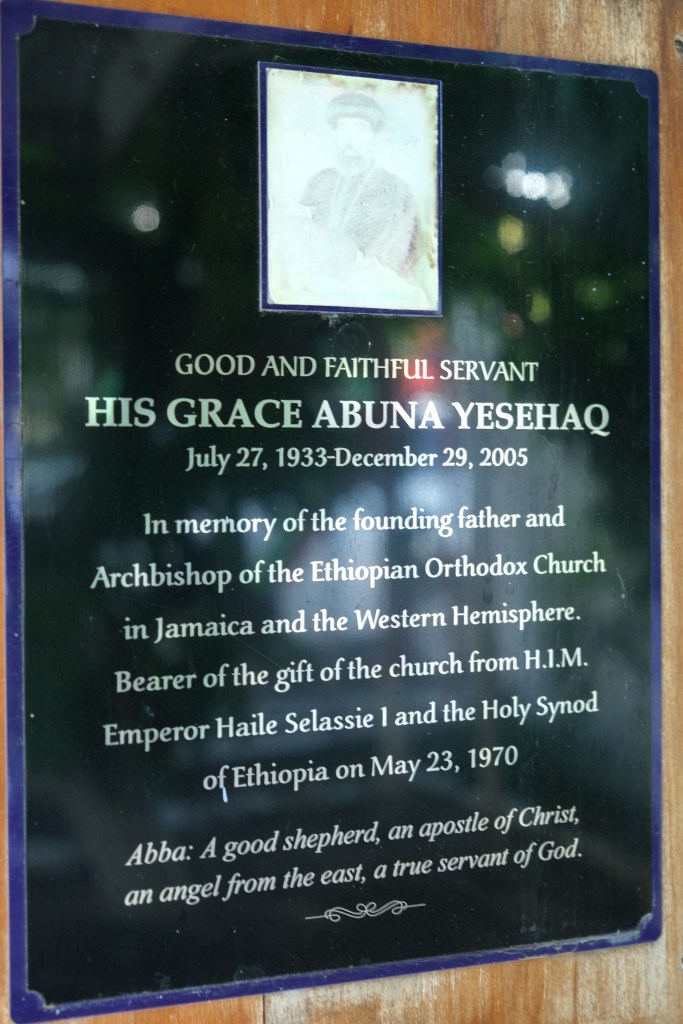

There on the premises at Maxfield Avenue are several institutions: the unfinished Holy Trinity cathedral (which has been under construction since 1995), the Holy Trinity Basic School (of which one classroom has been converted into a “temporary” church while the cathedral is being finished. Temporary, in this case, taking quite a long time), the Abuna Yesehaq Home for the Aged, and the tomb of Abuna Yesehaq. Abuna Yesehaq was the priest who Haile Selassie I sent to the West in the 1950s, establishing churches in Guyana, Trinidad, New York, and in Jamaica in 1970. He also spread the faith into the United Kingdom and South Africa, as well as smaller Caribbean islands.

From there, we traveled to the nearby St. Yesehaq (Isaac) Basic School, built by one of the priests from Holy Trinity while he was still a deacon, and named in honor of Abuna Yesehaq. We spoke to the principal there, recording a video with her, and taking some photographs.

Then the group split into two contingents, one returning to Holy Trinity, while Yoseph, Titi, and myself went to the Bob Marley Museum on Hope Road. This was once a mansion belonging to Bob Marley, where he built the original Tough Gong recording studio and recorded many classic roots Reggae albums for his own group and others. While we waited on our tour, I took pictures of the many vibrant murals all around the property, which is also home to the Bob Marley Foundation, Rita Marley Foundation, and Marley brands.

Our private VIP tour was provided by none other than Ricky Chaplain, a powerful Rastafari personality and one of the most memorable actors from the Bob Marley: One Love film, who is affectionately nicknamed “Ababa Bikela”, after one of Haile Selassie I’s bodyguards. Brother Ricky was the perfect tour guide for us, as he was able to movingly express the Rastafari nation’s sentiments towards His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I and Empress Menen, and connect Bob Marley’s mission on earth to this great reciprocal relationship of love, liberation, and civilization. He was a perfect communicator for our Ethiopian guests, bringing them a very strong sense of context for the things they’d seen here in Jamaica. Jamaica, the land where Imperial Ethiopian flags were visible everywhere, and Jamaican flags surprisingly rare, where pictures of the Emperor and Empress (on stickers, posters, banners, and painted on walls) far outnumbered the pictures of any Jamaican national heroes.

After the tour, we sat and reasoned with Ricky for a while, planning a future trip together to Ethiopia. One of many, if God so wills (be Igziabeher feqade).

From the Marley Museum, we met up with Teddy and another bredren, Haile Maryam “Chinna”. Together we traveled to August Town to visit a place called Judgment Yard, the base of Reggae superstar Sizzla Kalonji. When we arrived, we learned that Sizzla was not there. He’d played a show up north over the weekend and had not returned yet. We got a tour of the vast property, where Sizzla has built a series of pools for the local children to play in, and begun construction of restaurants, venues, museums, and such. There is also a Nyahbinghi tabernacle there. Clearly, he is determined to change the face of this neighborhood and positively influence its destiny.

Teddy got on the phone with Sizzla, whom he knew from prior interactions. He’d brought some donations to give him for the Sizzla Youth Foundation, so they needed to link. Over the phone, the two of them cooked up a new plan for Teddy to stay an extra week there at Judgment Yard. So, I got on my phone too and bought Teddy a new ticket, canceled his previous one, and that was that. These are the 21st century miracles that we take for granted these days.

We stopped at another place for Ital food (basically the only kind of food we ate on this trip) and it was delicious. The chef was another Rastafari bredren planning his own baptism in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and we may also have obligated ourselves to bring him to Ethiopia one day. After meeting Bongo Cecil on Saturday, that same conversation seemed to be happening a lot.

From there, Kes Haile Mikael brought us up to a place called Debre Zeit, in the same neighborhood as the Kingston Dub Club we’d visited the night before. This place was established in the 1970s as an Ethiopian Orthodox Rastafarian community, with many of the brethren living together on a communal patch of land, and a row of Rastafari craft shops based along the roadside. Now, most of them have moved on or passed away, and the land is shared with their relatives and others who are not all Orthodox or Rastafari, though the overall character of the place prevails. There is still one bredren keeping a shop there, Ras Haile Malekot, the Reggae singer, sound system selecta, craft vendor, and knitter of tams and belts.

We visited with Haile Malekot (whose name means, “Power of the Kingdom”) and another youth called Wolde Meskel (“Son of the Cross”) long into the night, and we did all of our souvenir shopping there. It was a good vibe and fitting for the last night of the trip, speaking joyfully of all we had seen, imagining the possibilities in the future for this place, and blessing the bredren there with our strength. It was truly One Love, over, under, around, and throughout this visit to Jamaica.

Day 9 – Tuesday, March 4th, 2025

We arose early again to attend Kidane at Holy Trinity, saying our farewells to Abba Samuel, the other clergy, and the residents of Abuna Yesehaq Home for the Aged.

There were several other bredren I hoped to link there in Kingston, ones who I’d met through the Association of Rastafari Creatives, but hadn’t yet had the chance to meet on this trip. It seemed like we might be able to make it happen, and we chased each other around a bit, but the plans kept changing and then we didn’t.

Instead, Kesis decided to bring us for an Ital breakfast at the Country Farm House, a foundational Ital kitchen here in Jamaica. While we enjoyed this trip’s final meal of Jamaican Rastafari Ital cooking, the priest received a phone call. Sizzla Kalonji wanted to meet with us before we went to the airport.

So, we went to a neighborhood nearby, stopping in front of a large and well-appointed house. There we met the famous Reggae singer, who gave us his Ethiopian name, Fikre Maryam (Love of Mary). He insisted on giving the three of us a ride to the airport.

This is where we got to witness the spiritual power of Sizzla Kalonji—Fikre Maryam—who humbly took into his vehicle 3 strangers and 1 acquaintance (Teddy), without any bodyguard or bullet proof vest (and I’ve seen other Jamaican musicians wearing these in comparably much safer places) to do the kindness of taking us all to the airport. We also witnessed the social power of Sizzla, who drove through the city with his blinkers on, bypassing the police checkpoints like a government dignitary.

He didn’t speak much. Yoseph and Titi weren’t sure who he was, and asked if he was a music producer, to which he replied that he was indeed a producer, and an artist, and an engineer, and a mechanic, etc. A well-educated and multi-talented man, but that was about all we got out of him by way of conversation. He dropped us at the airport and took a couple pictures with us, before being swamped by the crowds who recognized him and wanted their own selfies with the man. He quickly had to exit this attention, taking Teddy with him. And there we were.

Inside the airport, Yoseph and Titi were politely approached by people who wanted to know who we were and why we were being dropped off at the airport by Sizzla himself. Now Yoseph and Titi really wanted to know who this man was. So, I played them a few of his songs and read out some facts about his success in the music industry. They said, “Wow, this guy is a serious musician.”

Later, on the plane, the man seated next to them was one who’d seen us with Sizzla and was very impressed, just going on and on about Sizzla, asking them questions and showing them videos, and such. I think now they got the idea of what a big deal this really was.

And that’s about the end of my stories from this trip. Transferring in Miami, the land of Jamaica began to fade away, as our airplane companions from Kingston dispersed to their various other cities, and we to ours. I saw a girl in a Bob Marley shirt and told her, “nice shirt”.

The weather was cold in Seattle when we arrived around midnight, and—just like that—we were fully finished with our trip. Bumping into a Kenyan friend of mine who works at the airport further helped to reenforce the idea that it’s a small world. I grabbed a cup of coffee to keep me awake and spent two hours on the drive home talking to my brother in Kenya and my sistren Mama Askale Selassie in Shashemane, Ethiopia, working on plans for the future.

It is indeed a small world, and a good one.

Just the Beginning

We left Teddy there in Jamaica and he stayed with Sizzla for another week, met the Marley brothers at Jo Mersa’s birthday party and memorial event, and did some good works supporting the Church and the Sizzla Youth Foundation.

Titi and Yoseph and I saw each other at church on Sunday and we were all exhausted. In fact, it took longer for us to recover from this whirlwind trip than the trip itself had taken. We had a lot of stories to share with our clergy and friends at St. Maryam and St. Arseima in Lynnwood, Washington. I still have those 1000 photos and 100 videos, and a whole lot of follow-ups to do on all the plans we made while we were there.

This is just the beginning.